Quickstart¶

Setting up Ella¶

This tutorial will guide you through the process of creating and deploying your first Ella-based site. Since Ella is a CMS, we will create a blog. This first step will take us through setting up our environment, installing all the dependencies and kicking off the project. Before you dive into it, we suggest you go through the official Django tutorial to get yourself familiar with Django since we will be relying on that.

Dependencies¶

We assume that python, setuptools and python-imaging (PIL) are

installed on your system directly since they can be non-trivial to install the

python way. We will be working with pip and virtualenv which are great

tools for any Python project.

Note

We will not cover any version control, but we strongly advise you use some (we prefer GIT) to keep track of your emerging project.

First we need to install virtualenv (under root):

easy_install virtualenv

Now we can create and activate a virtualenv where our project and all related code will reside:

virtualenv ella_sandbox

source ella_sandbox/bin/activate

Next, install Ella into your fresh virtualenv. Ella has all it’s dependencies

covered in it’s setup, so it’s fairly sufficent to run following command

using pip:

pip install ella

After these steps, everything required is ready and we can create a new Django project using Ella in standard Django way:

mkdir ellablog

cd ellablog

django-admin.py startproject ellablog

settings.py¶

Our first step in actual code will be adding Ella to your project’s

INSTALLED_APPS along with some required settings, the resulting values

(unchanged values are omitted) should look similar to this:

...

INSTALLED_APPS = (

'django.contrib.admin',

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.sites',

'django.contrib.redirects',

'ella.core',

'ella.photos',

'ella.articles',

)

...

In order to create our new blog, we are gonna need some HTML templates showing

post listings, post details, hompage etc. Therefore, we have to tell

Django, where to look for those templates. This settings are kept in

settings.py contained in root of our project. Second, we need to specify

a directory + URL used to serve media files from:

Note

Media files and static files are not the very same thing. We consider media files those, that are uploaded dynamically by users, e.g. main article photos. On the other hand, static files usually don’t change and their common representatives include CSS styleseets, JS sources etc.

from os.path import join, dirname

PROJECT_ROOT = dirname(__file__)

# set the templates directory

TEMPLATE_DIRS = (

join(PROJECT_ROOT, 'templates'),

)

# give Django media settings

MEDIA_ROOT = join(PROJECT_ROOT, 'media')

MEDIA_URL = '/media/'

This will tell Django, that it should look for the templates in directory

templates which is located in the root of the project directory. And

store the media in PROJECT_ROOT/media/ directory.

urls.py¶

Last thing to configure is the URL mappings. We want to include ella.core.urls

which handle all the Ella magic but also create some mappings that will

serve our static files (and static files for admin) in the development server.

Note that these patterns for static files will work only when DEBUG mode

is turned on since it would be rather inefficent in production (for more on

this topic, see Managing static files section in Django docs). In similar

fashion, serve also media files discussed in previous paragraph:

from django.conf.urls.defaults import *

from django.conf import settings

from django.contrib import admin

from django.contrib.staticfiles.urls import staticfiles_urlpatterns

# make sure to import ella error handlers

from ella.core.urls import handler404, handler500

# register apps for Django admin and let the apps do any initialization they need

from ella.utils.installedapps import call_modules

call_modules(('admin', 'register', ))

urlpatterns = patterns('',)

# actual URL mappings

urlpatterns += patterns('',

# serve media files

(r'^%s/(?P<path>.*)$' % settings.MEDIA_URL, 'django.views.static.serve', { 'document_root': settings.MEDIA_ROOT, 'show_indexes': True }),

# run Django admin

(r'^admin/', include(admin.site.urls)),

# enable Ella

(r'^', include('ella.core.urls')),

) + staticfiles_urlpatterns()

Note

Instead of calling admin.autodiscover we are using Ella’s

call_modules which is a more generic version of the same thing. and

allows us to load additional modules - namely register.py where, by

convention all Ella apps put the codethey need for their initialization

(connecting signal handlers, registering custom

urls etc.)

Database¶

Last configuration step is the database settings. Ella supports all Django DB backends. Example configuration for MySQL can look like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.mysql',

'NAME': 'ellablog',

'USER': 'user',

'PASSWORD': '',

'HOST': '',

'PORT': '',

}

}

To make this work, you should make appropriate database by your custom

DB-related tool (such as command-line tool mysql in Linux-like operating

systems). After creating the database, you can proceed with creating all the

required tables by Django for you (and admin user during this process):

python manage.py syncdb

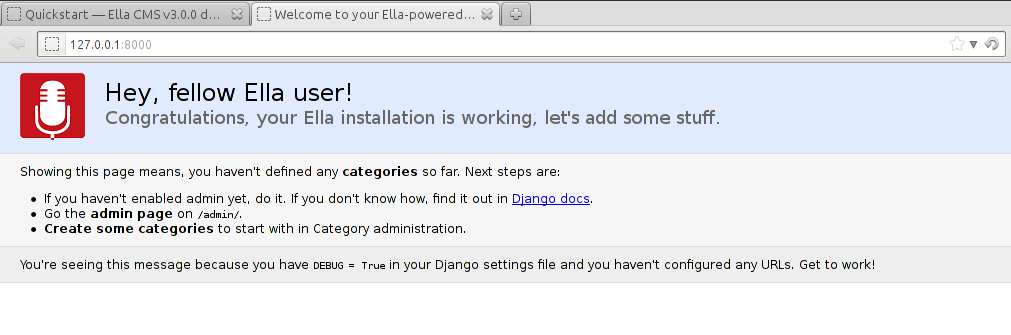

Congratulations, you should have a working Ella project. If you start the development server by typing:

python manage.py runserver

try to load the site’s root. If everything worked out, you should get a welcome screen looking similar to this:

Now when we have a working project, we need to actually create the site in the

admin interface. To use it, go to /admin/ and log in using credentials

you entered when creating your superuser account during the syncdb command.

While being there we will also create an article - our very first blog post so

that we can actually have something to work with in our templates in the next

step of the tutorial.

Note

If you are impatient to start, just play around with the admin to create

one instance of ella.core.models.Category to get the root of the web

working and then one ella.articles.models.Article published in that

category (you might need to create additional model like Author on the

way).

First we need some theory on how Ella handles sites, categories and published objects though.

Ella sites and categories¶

Ella was designed to serve several sites from a single database. It does so by

using Django’s built-in sites framework. The sites app creates a

default Site called example.com during the syncdb command. Just

rename the domain name to relevant value and you will have an Ella site,

just empty.

Within sites, Ella organizes content into categories. Categories (instances

of ella.core.models.Category) are organized in a tree for each site. Every

site needs to have exactly one what we call root category - a category without

a parent. This category then represents the root of the website (/).

Categories are represented by their tree_path - a path of slugs from

root category, for example with categories layout:

Ella Blog

About

Technology

Concepts

Django

Django applications

Typical deployment env

the tree_path values would be:

| Category | tree_path attribute |

|---|---|

| Ella Blog | |

| About | about |

| Technology | technology |

| Concepts | technology/concepts |

| Django | technology/django |

| Django applications | technology/django/django-applications |

| Typical deployment env | technology/typical-deployment-env |

Category‘s URL is it’s tree_path (which is what makes the root category

the root of the site) and every post in Ella belongs to one or more categories,

nothing shall exist outside of the category tree.

Publishable object¶

The main objective of Ella is publishing content. Ella together with it’s

plugins provides several types of content (Article,

Gallery, Quiz, ...) and can be easily extended to add more (just define

the model) or used with existing models.

For ease of manipulation and efficiency, all content models inherit from

ella.core.models.Publishable. This base class has all the fields needed to

display a listing of the content object (title, description, slug,

photo), basic metadata (category, authors, source). When using

Ella API you will always receive an instance of the actual class (Article)

and not the base class (Publishable). If you have access to only a

Publishable instance the target property will return instance of the

correct class (it holds a reference to it’s ContentType).

Information about publication are also kept on the Publishable model

(attributes published, publish_from, publish_to and static).

All these information together are used to create an URL for the object

which will point to it’s detail (e.g. article content). There are two types

of publication with slightly different use cases:

time-based has URL containing the date of publishing and should be used for objects that have some relevance to date (most of the content presumably since Ella was designed to power magazines and news sites). The URL of an object published in time-based way will look like:

/category/tree/path/[YEAR]/[MONTH]/[DAY]/[CONTENT_TYPE_NAME]/slug/

so for example:

/about/2007/08/11/ella-first-in-production/

static has no date in it’s URL and should be used for objects with universal validity. URL of statically published objects contains a primary key reference to avoid namespace clashes:

/category/tree/path/[PK]-slug/

for example:

/about/1-ella-first-in-production/

Just setting up publish information for a Publishable object makes it

visible (starting from publish_from) but doesn’t make it appear in any

listing in any Category. For that you need to specify in which categories

you want it listed.

Listing object¶

ella.core.models.Listing instances carry the information in which Category

and when should be a publishable object listed - it enables users to list the

object in as many categories as they wish at arbitrary times (but not sooner

that the Publishable.publish_from).

By default, listings in the root category only contain Listings specifically

targeted there whereas listings for any subcategory also contains all the

listings of it’s subcategories. This is a model we found most useful when

working with large sites where the site’s homepage needs to be controlled

closely by editors and the interim categories only serve as aggregators of all

the content published in them either directly or via a subcategory.

Creating a site¶

Now you should have enough information to be able to start exploring the

admin (found on /admin/) and create your own site and it’s first post.

You will know that you were succesfull if you manage to create and publish an

article whose URL gives you a TemplateDoesNotExist exception upon

accessing - that means we are ready to create some templates.

Basic templates¶

Now that we have some sample data to work with we can finally start creating the templates we need to get the site running.

Note

For more information on what templates Ella uses and what context is passed in, have a look at Template overview.

page/category.html¶

First we will create a template rendering a category: page/category.html.

This is a default template that will be used for all categories if their

specific template (one with their path) isn’t found. The two most important

variables in the context we want to use is {{ category }} containing the

Category model itself and {{ listings }} containing a list of

Listing objects for that category ordered by publish_from and/or

priority.

The basic template will look like:

<h1>Welcome to category {{ category.title }}</h1>

<p>{{ category.description }}</p>

{% for listing in listings %}

<p>

<a href="{{ listing.get_absolute_url }}">{{ listing.publishable.title }}</a>

{{ listing.publishable.description|safe }}

</p>

{% endfor %}

That will render the category title, description and a list of objects published

in that category. Upon accessing / you should then see the name of the

category and the article you created in administration.

page/listing.html¶

This template represents the archive, it gets the same context as

page/category.html and the same code can be used. We will use the same code:

{% extends "page/category.html" %}

page/object.html¶

As with page/category.html, page/object.html is a fallback template that

will be used for rendering any object if more suitable template isn’t found.

In real life we will probably have different templates for different content

types, but to verify the concept and get us started a simple template should

be enough:

<h1>{{ object.title }}</h1>

<p>Published on {{ placement.publish_from|date }} in category: <a href="{{ category.get_absolute_url }}">{{ category }}</a></p>

{% render object.description %}

This template will have access to the actual Publishable subclass instance

(Article in our case), as opposed to page/category.html and

page/listing.html which only gets instance of Publishable by default.

Note the use of {% render %} templatetag that is used to render rich-text

fields (which object.description is) thorought Ella.

Error pages¶

By importing handler404 and handler500 in our urls.py, we turned

over the control of error pages to Ella. This means that we need to create two

additional templates: page/404.html:

<h1>Oops, nothing here</h1>

and page/500.html:

<h1>If you see this, let us please know how you did it, thanks!</h1>

Now that we have a set of rudimentary templates, we can try doing something useful with them.

Enhancing templates¶

Since Ella is a regular Django application, even it’s templates are just plain Django templates. Therefore we just refer you to other sources and Common gotchas & FAQs section to learn more about the templating language and it’s best practices, we will try to focus just on Ella-specific parts.

Boxes¶

First change we will make is abstract the rendering of the object listing on

category homepage and archive. To do this, Ella provides a Box for

individual objects. It’s primary use is as a

templatetag. Boxes can be rendered

for objects accessible through a variable or through a database lookup:

{% box <box_name> for <object> %}{% endbox %}

or

{% box <box_name> for <app.model> with <field> <value> %}{% endbox %}

What {% box %} does is a little more then fancy include - it retrieves the

object, find the appropriate template and renders that with object-specific

context. The context can be quite different for an Article or Photo gallery.

Boxes are usually used throughout an Ella site to provide maximum flexibility

in rendering objects and also for embedding objects into rich text fields stored

in the database (in text of an article for example). Some applications (

Defining positions on the page for example) also use boxes to represent objects.

To create our first box, we just need to create a template called

box/listing.html containing:

<p>

<a href="{{ object.get_absolute_url }}">{{ object.title }}</a>

{% render object.description %}

</p>

And change page/category.html to use the box instead of manually specifying

the output:

<h1>Welcome to category {{ category.title }}</h1>

<p>{{ category.description }}</p>

{% for listing in listings %}

{% box listing for listing %}{% endbox %}

{% endfor %}

If you still struggle, why the bloody Box is used instead of standard

{% include SOMETHING %}, keep in mind following advantages:

They know which template to use with proper fallback engine.

- The provide class-specific context so that an Article can have

different context than Photo.

Template fallback mechanisms¶

In last step we created a few templates that should suffice for an entire site based on Ella. In real life you probably wouldn’t want every category and every object to share the same template. Ella provides a simple mechanism to target your templates more directly.

Let’s say that we want to create a specific template for rendering articles,

just create a template called page/content_type/articles.article/object.html

and you are done - next time you visit some article’s URL, this template will

get rendered instead of your page/object.html. This template would be a

good place to render the text of an article for example:

{% extends "page/object.html" %}

{% block content %}

{% render object.content %}

{% endblock %}

Now if you just define the appropriate block in your page/object.html:

<h1>{{ object.title }}</h1>

<p>Published on {{ object.publish_from|date }} in category: <a href="{{ category.get_absolute_url }}">{{ category }}</a></p>

{% render object.description %}

{% block content %}{% endblock %}

You should be able to see your article’s text on the web.

Another way you can override your templates is based on Category. For

example if you want to create a custom template for your root category (and

your root category’s slug is ella-blog), just create one called

page/category/ella-blog/category.html:

<h1>Welcome to site {{ category.site }}</h1>

<p>{{ category.description }}</p>

{% for listing in listings %}

{% box listing for listing %}{% endbox %}

{% endfor %}

You will be greeted into the site and not your root category next time you visit the root of your blog. Just create any subcategory to check it will remain unaffected.

You can use the same simple mechanism (creating new templates) to change the look of your boxes for individual objects as well.

Note

For more detailed explanation of all the possible template names, have a look at Views, Template overview and Templatetags documentation.